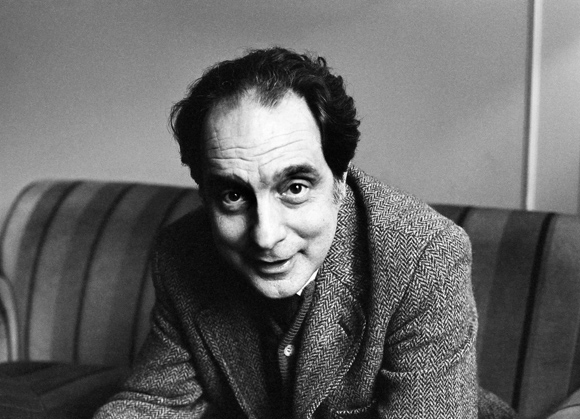

In 1984, the Italian intellectual Italo Calvino was invited by Harvard University to conduct its Charles Eliot Norton Poetry Lectures cycle. The author of "The Path to the Nest of Spiders," "If on a Winter's Night a Traveler...," "The Cloven Viscount," and other post-war classics decided upon the theme of "Six Propositions for the New Millennium." Calvino was only able to finish five of them. According to his wife Esther, the sixth, "Consistency" was never completed in as much as he died of cerebral hemorrhage on September 19, 1985, one week before the conferences were to begin. The propositions were directed primarily at the future development of novel composition, but contain lessons applicable to our lives, which are, in a world of exploding aspirations and desires, increasingly novel in and of themselves.

Levity

Calvino began the discourse on "lightness" by noting that his own literary efforts had consisted primarily of relieving the weight bearing upon humans, celestial bodies and cities. At those moments when the human condition appears condemned to heaviness, Calvino said he attempted, like Perseus, to fly toward another space, to change his focus, to see the world through an alternative looking glass, using a different logic, other methods of investigation and verification.

Through the centuries, he maintained, literature has been characterized by two tendencies: one which construed language as an element without weight, like a cloud or a field of magnetic impulses; the other which used it to communicate weight, density, and the concrete nature of bodies and sensations.

"The second industrial revolution does not present itself as did the first," he noted, "with overpowering images of presses and steel furnaces, rather as bytes in a flux of information, which run through circuits in the form of electronic impulses. Machines of steel still exist, but they obey bytes without weight."

He goes on to recount an anecdote composed by Bocaccio about the Florentine poet Guido Cavalcanti.

Despite being "rich and elegant," Cavalcanti was unpopular with the young lions of Florence for he chose not to cavort with them and because they suspected him of sacrilegious thoughts. Once, they decided to test

the poet, surrounding him on horseback as he meditated atop a tomb in the piazza of Santa Reparata. "Guido," they sought to intimidate him, "you reject our company, but when you discover God does not exist, what will you do?"

The poet replied, "Sirs, in your house [of death], you can tell me what you please," before escaping them, using the weighty tomb as a springboard for a leap to safety.

"If I had to chose a single symbol with which we might approach the new millennium," Calvino asserted, "it would be this one: the agile, sudden jump of the poet/philosopher rising above the heaviness of the world, demonstrating that in its gravity lies the secret of levity, whilst that which many consider the vitality of the times, noisy, aggressive, angry, and thundering, pertains to the kingdom of the dead, like a cemetery of rusty cars."

Speed

In his second proposition, Calvino broached the question of speed and the differences between its physical and mental manifestations. A story, he asserted, is a horse, a means of transportation with its own pace and itinerary. "The horse as a symbol of speed, even mental speed," he wrote, "marks the entirety of literature, and presages all that is problematic on our technological horizon."

Today, he observed, other, faster media triumph to the point where we run the risk of "flattening all communication into a uniform, homogeneous crust."

Faced with this challenge, it is the job of literature to establish lines of communication between what is different, and exalt that difference. If the machine age has imposed speed as a measurable value, the records of which mark the history of progress, "mental speed cannot be measured and does not invite confrontations or competitions. It has its own value -- namely the pleasure it produces in those sensible to it -- not for its practical utility"

Only mental speed possesses a tool for arresting civilization's race with time: the digression. "If a straight line is the shortest distance between two inevitable and fatal points, digressions stretch them out; and those digressions return, thereby becoming longer, more complex, tangled, tortured and so fast themselves as to become derailed. In doing so, perhaps death loses our scent."

Calvino opposes speed for its own sake and likens our obsession with it to one with death itself. Only the meditative nature of literature, drawn from life-engendering creativity, can delay it.

The genie of modern velocity, of course, cannot be returned to the bottle, but writers [and everybody else] "should keep in mind its rhythmic components: that of Mercury and that of Vulcan, a message of immediacy obtained through patient and meticulous labors; an instantaneous intuition which, barely formulated, acquires the fullness which permits its perception by any other means."

Exactitude

"I have the impression," he stated, "that language is used approximately, casually, negligently, which causes an intolerable anxiety in me." Calvino likened this condition to a plague affecting language so that it "loses all cognitivity and immediacy, like an automatism which tends to level expression into its most generic forms..."

But more importantly for our time, this pestilence affects the world of imagery as well. "We live under a rain of uninterrupted images; the most potent mass media do nothing more than transform and multiply the world of images which, in large part, lack the internal necessity that should characterize them, like form and meaning, like the capacity to attract one's attention, a richness of potential signifiers."

The world, he claimed, is ever-dissolving into a cloud of heat, precipitating a whirlwind of entropy. But this process lends itself to intervals of order and form, privileged points from which a plan and perspective can be perceived. "The literary work is one of those small points of privilege where things crystallize into a form which acquires such meaning."

Just as the understanding of speed requires deliberate labor, so the search for exactness takes two roads: one which reduces events to abstract schemes and the other which uses words to express, with the most precision possible, the meaning of things.

"I think we are always in the hunt for something hidden, a potential or hypothetical, the tracks of which can be seen on the surface of things, and which we follow. I think our most rudimentary mental mechanisms repeat themselves, from our Paleolithic hunter-gatherer forefathers, throughout the cultures of humanity. The word unites these tracks with the invisible entity, the absent quantity, the thing desired or feared, like a fragile bridge improvised across the void."

Calvino urged the exact use of language because it would permit us to approach things, present or absent, "with discretion, attention, and caution, with the respect for those things which communicate without words."

Visibility

The fourth conference Calvino gave was to start with the following premise: Fantasy is a place where it rains.

"We can distinguish two types of imaginative processes," he maintained. "One that uses the word as a point of departure, another which derives inspiration from the image."

As a writer, Calvino fell into the latter category. "In conjuring up a story, the first thing that comes to my mind is an image that, for whatever reason, is char

ged with significance for me."

Where do the images raining upon the imagination come from? he asked and then answered: "Writers establish links with earthly emissaries such as the individual or collective unconscious, sensations emerging from lost time, epiphanies, or the concentration of being on a certain point or moment. I

t is a case of processes which, although not born in heaven, escape from the world of our intentions, from our control, granting the individual a kind of transcendence."

For Calvino, the imagination is a form of identification with the "soul of the world." He worried about its future in the so-called "civilization of the image." He saw it threatened by the deluge of prefabricated pictures bombarding us all.

"Our memory is coated with image fragments, like a depository of waste, where it is becoming increasingly difficult for one figure, amidst so many, to acquire full relief. If

I've included visibility in my list of values that should be saved in the next millennium, it is as a warning to the danger of losing a fundamental human faculty: To focus upon images with our eyes closed, to make them jump forth in full color and form from the alignment of black letters on a white page, to think in images."

Multiplicity

Calvino argued for a continuation of the modern novel as an open encyclopedic adventure in opposition to the unitary, closed system which characterized the form in its medieval incarnation.

"Knowledge as multiplicity is the thread which unites all the masterpieces, both modern and post-modern, a thread which transcends all labels. This I would like to see developed further in the coming millennium."

He maintained that the best novels encompassed the convergence of a multiplicity of interpretive methods, modes of thought, and styles of expression. What is important, Calvino argued, is not that the story close harmoniously, rather that its centrifugal forces liberate "linguistic plurality as a guarantee of impartiality."

"Somebody," he concluded, "might argue that the closer a work leans toward a multiplicity of possibilities, the farther it gets from the unified self who is writing, their inner sincerity, the discovery of their own truth. Bu the opposite is true. What are we but a combination of experiences, information, readings and imaginings? Each life is an encyclopedia, a library, a showcase of styles which can be continuously mixed an reordered into all the possible forms."